With the kind permission of the author, One Man’s Addiction to Flying will be published online each and every day. After the online publication is completed, a PDF version will be available to download.

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – Introduction is here.

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – The War Years (Part One) is here.

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – The War Years (Part Two) is here.

[Although there is a little bit of repetition here this letter to my Grandparents gives a little more detail and is great to have the original letter which is now some 76 years old.]

23 Squadron

R.A.F.

B.N.A.F.

18/2/1944

Dear Mother and Dad,

I think I might as well start an ordinary and, I trust, comparatively interesting letter, which I find quite impossible on an air letter card. Heaven knows how long it will take to get to you, if it ever does, as it will come by sea.

I can’t really tell you an awful lot about the trip out here. Suffice is to say that we were lunching at Algiers within 12-hours of leaving England, and that Algiers, as I have remarked before, is one town. We spent three days there this site and found our way around quite a bit. Tunis we managed to get through fairly quickly, but had time to look at the dock area which is a complete and utter shambles. We stayed the night at a peacetime luxury hotel – not quite so luxurious now, but still reasonable. One discomfort is the complete lack – throughout Algeria and Tunisia – of any hot water.

Anyway, after much cursing and binding, we reached our island. We were forced to spend two days in Cagliari and what a two days. It is, I believe, one or the most scientifically bombed areas in this theatre of war, and it certainly rates very high in my estimation as the most depressing town I’ve ever seen – far worse than Malta. There is literally nothing stirring at all. The Americane are running the nearby aerodrone and the one consolation was their rations which are excellent. We had tinned fruit for every meal, and you can guess how that would suit me. There was no light or heat anywhere, and the only course available at dusk was to go to bed, where it was at least warm. The Yanks have their last meal of the day at 5.30, and it leaves a complete blank for the rest of the evening. The weather was very had

…

and, after two days of it, Greg and I decided to take the drastic action of ‘hitching’ across the mountains on a truck. It was quite the coldest ride I’ve ever had – there was over a foot of snow on the ground and we came through blizzards and rain and what have you – all in an open-backed Yank 6-wheeler with no seats in. It took us 7-hours to get here, by which time we were more or less numb and extremely hungry, as we started before tea and didn’t get in till after 10. However, we rapidly knocked back a night flying supper and several very large whiskies, and the warmth of our welcome was sufficient to thaw us out pretty thoroughly. Anyway, we both agreed that it was better than hanging around that deadly hole waiting for the weather to clear.

We are the first crew to return to the Squadron from U.K. and everyone takes a very good view. My Flight-Sergeant who came out with us is still here out, and was very glad to see me, as are all the ground crew we brought Their chances of getting home are nil for 3-years, but I think they feel not quite so deserted if air crew come back for a second dose. Apart from that sentiment, they all think we are completely mad to leave home again.

The Squadron’s reputation stands as high as ever it did, and that’s saying quite a lot. They still fly hard and play even harder, and its no line-shoot to say that “the fighting 23rd” is a by- word in these parts.

We are stationed on an old Italian aerodrome, which is, like most of them, composed of very fine aerodrome buildings and an appalling aerodrome. However, it is sufficiently good to operate from. The squadron aircrew are billeted in an ex-Italian Fascist Headquarters, still under construction. It’s really a pity they were not allowed to finish it, as it would have been rather fine. However, we are in one

…

of the finished bits, and are very comfortable. I am sharing a room with Greg and our windows face South across the bay and we look out across the bay to the mountains. The sea is only about 100-yards from the window, and the view is wizard. Unfortunately, most of the glass is missing, as there have been several sea mines go off in the bay after drifting ashore, and the RAF has been a bit playful around here too. Luckily it’s only the North winds that are cold, and as they are almost in the North they don’t worry us much. The central heating we manage to get going on most days with scrounged fuel, and this also supplies us with hot showers. The weather in distinctly colder than Malta, probably because these damn great mountains have something to do with it, and also because prevailing winds come straight down from the Alps. However, I’ve no doubt the end of this month will see us start to swelter a bit.

We have arranged to hire a 27-foot sailing boat from a Type across the bay, and that should be absolutely smashing for the odd day off.

The Italians have more or less deserted large number of Yugoslav prisoners of war who were here on the island. The poor beggars appear to be no-one’s care at the moment, and they are practically starving. We employ a dozen in the mess here as batmen, and they do a very good job too. They do all our washing for us, and do it as well as most laundries.

My Italian is not so hot as yet. We went out on a scrounging expedition yesterday afternoon and came back with two Turkeys, four chickens, 50 eggs, and a basket of lemons. Practically all trade is done in cigarettes or food. If we give them money, they’ve got nothing to spend it on anyhow. A few of the peasants

…

have a smattering of French or German, and the mixed language that flies around at the bartering is just nobodies business. However, with much dumb show and nattering, we make out somehow.

The rate of exchange in 400 lira to the £ and 10 woodbines will fetch 50 lira in the black market in the Town. Eggs cost us 5 cigarettes. Lemons can be picked fresh from the trees at 1 ½ lira each but there are no oranges in the North of the island.

We have ‘egg orgies’ owing to their plentifulness, and it is no uncommon aight to see someone consume six fried eggs with no trimmings at two in the morning after some celebration. We got through 40 the other night. All the necessaries are a tin plate, some margarine pinched from the Mess, and a solid Meths-stove.

I have taken over a new aeroplane. ‘A’ and christened her Susan II. We hope to do our first ops as soon as we got some reasonable weather. I took her on a test trip round Sicily the other day and I had a wonderful time looking at all the places where we used to get into trouble last year. It’s amazing how different it looks in daylight.

Our only worry at the moment is that we’re in a pretty hectic malaria belt, but we may be moved before the danger period cames, no it’s no good worrying.

Well, I reckon that’s enough for this time, else I shan’t have anything left to write about. I hope you’ll pass this round, because I’ll never be able to write it all again. It will probably come home to a returning aircrew, who I hope will remember to post it in England.

Love to you all at home.

Caption

Egypt, March’44. With Bill Shankland and Abdul in front of the Sphinx and Giza Pyramids, Cairo.

I had scarcely properly settled in when I received a signal posting me to a Junior Commander’s Course in Cairo. This meant a journey of 1500 miles (the old American Taxi Service again) for a fortnight of luxury living on one of Tommy Cook’s [Thomas Cook & Son] houseboats on the Nile, attending lectures sporadically (no one was really interested) and spending the remaining hours in the Turf Club and Gezira Club of which we were made Hon. Members. There were no exams and I returned no wiser, but considerably poorer, than when I left. I ‘did’ the pyramids etc. on H.M. Government and flew 1500 miles back again. A funny old war indeed. From our houseboat we were rather amazed to watch the local women coming down to the river bank, defecating, washing themselves, and then filling their pots with drinking water from the river. We had strict warning that if we fell into the river it meant either a stomach-pump immediately or being dead from the dreaded Bilhartzia within forty-eight hours. The Gippos must have bred some pretty tough women.

Mementoes of second overseas tour

The American Squadron to whom I referred earlier were the only other allied unit on the island, everyone else having gone up North after the Germans. They were a friendly crowd but with odd habits. When we threw a Mess party and invited them over, we got rather drunk, as usual, and played silly games like rugger in the Mess. Not for them. When THEY threw a party the invited the entire contents of the local brothel including Madame. The standard drink was medicinal alcohol, of which they had unlimited supplies, laced with anything available – probably orange or tomato juice. Either way it was lethal. After an hour or so our hosts departed to their quarters with their ‘guests’ and we were left with our hangovers. Every one to their choice.

On one visit to a pub in our local village, Sassari, I must have drunk out of a dirty glass and I had to go to the local medical unit with a horrid throat.

Unfortunately for me, the only doctor on the island was American. Diphtheria had been eradicated in the States for some years and he failed to recognise the symptoms, so I was treated for tonsillitis. I was delirious for several days and they had to keep clearing my throat to enable me to breathe. My doctor at home, later, said that untreated diphtheria was nearly always fatal. It almost was.

By this time the invasion of Europe was imminent and it was apparently felt that we would be of more use flying from the U.K. again. We therefore left Alghero and flew our aircraft to Blida, the airport for Algiers, where we abandoned them. We eventually embarked on the S.S. Mooltan, 20,000 tons, a very luxurious liner, previously on the India run and still with her original crew. We duly set off in a fast, unescorted convoy bound for the Clyde. When we were well out in the Atlantic, our steering gear failed and we turned sharply towards an enormous liner in the outside column. Sirens blew and, with life-jackets on, we waited for the big bang. Fortunately we missed her, slowed to a stop, and sat quietly on the sea watching the rest of the convoy depart over the horizon. We were there for some time, during which we had a Sunday Service. Seldom has the hymn ‘For those in peril on the sea’ been more enthusiastically sung.

[Dad said they were just waiting for a U-Boat to appear and put a torpedo into them. A terrifying wait sitting quite helplessly in an empty sea.]

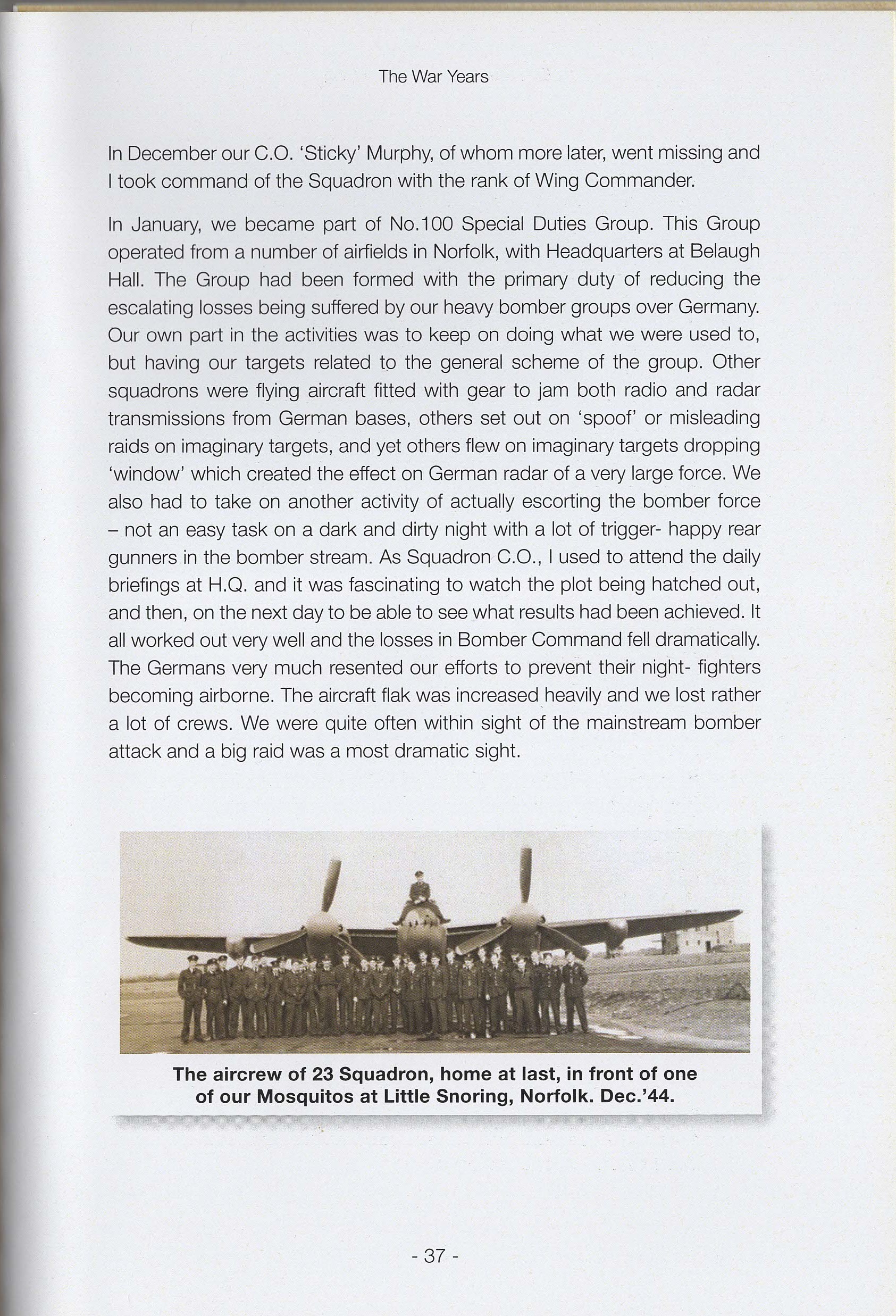

We anchored off Gourock on 29 May and on 1 June, as C.O. of the troops, I received a signal instructing the Squadron to report to RAF Little Snoring. When I told the gang our destination there was total disbelief and it was only when we climbed out of the train at Fakenham that the drivers of the buses confirmed that there was indeed such a place.

Having got ourselves bedded in, we received disembarkation leave and went on our different ways. I had felt unwell ever since my attack of ‘tonsillitis’, running some very high temperatures. I went for a check-up with my own doctor in Leicester and he first thought that I had caught polio and I was whipped into the Isolation Hospital. After many swabs and check-ups the health authority decided that I was suffering from the after effects of untreated diphtheria. By this time my eyesight was pretty useless and my legs had ceased to function. I was transferred to the RAF re-habilitation unit at Loughborough College, run by Dan Maskell of subsequent tennis fame. I had to learn to walk again, helped by with lots of massage from attractive nurses and swimming sessions with even more attractive ones. At the end of September I went for an RAF medical examination and (here I have to admit rather shamefacedly, to my mild disappointment) I was passed fit for flying duties and re-joined my Squadron on 7 October.

The European picture had changed considerably since we had left the U.K. and our targets were now principally in Germany and all rather heavily defended. In December we were fitted with radar and I took on a new radar operator, Hugh Boland, who was mad as a hatter and totally without a trace of fear. As we were crossing the enemy coast amid curtains of flak, he would laugh out loud and say, “Gosh, isn’t that pretty” – and he meant it!. He also carried a flute stuck in his flying jacket and would play happily to himself until I told him to belt up and find out where we were. His hobby on the ground was making up anything explosive such as bombs and rockets. I remember that he made a sort of Verey Pistol, and on the way home from a rather wild night in Norwich, during which we had stormed the Castle, he sat on the back step of the aircrew bus firing Verey lights along the road at following traffic. Judging by their evasive action, it must have been quite upsetting, seeing these coloured lights bouncing along the road towards them. To be frank, in the aircraft I would sooner have had a navigator who was as frightened as I was, but he did enjoy it so much.

[My understanding of this or a similar story was when a particularly impatient motorist was trying to pass their bus and Hugh had fired his Verey Pistol at him and he had to swerve off the road to avoid the flare. This resulted in a Sergeant from the local Constabulary visiting the base the next morning, asking questions about the possibility of men from the Squadron being responsible for the vehicle running off the road. Father, with a twinkle in his eye, explained that it was most unlikely that any of his men were involved in such an alleged incident and was amazed that the driver had seen what he claimed were lights bouncing down the road towards him. He politely asked whether the said driver had possibly been drinking. Nothing further was heard from the police on the matter. This also reminds me of another tale I heard concerning a couple of his pilots who had gone into Fakenham on their night off and having had such a good night out had lost track of time and missed the last bus back to the aerodrome. Rather than facing a lengthy walk in the dark, they had come across a steam roller which had its boiler still lit, but was dampened down for the night. They worked out how to fire the boiler up and to work the simple controls to enable them to drive the vehicle, somewhat slowly home. The unfortunate result of this adventure was that they had fallen asleep or lost control of the steam roller on arrival at the base and had run through a perimeter fence and then on through a bicycle shed flattening several of the Station bikes inside. The steam roller had then hit the stone steps of the Mess hall where it stalled. Where upon the two pilots duly abandoned it and fled. There was even more collateral damage as the next morning was an official visit from the ‘Queen Bee’ of the WAAFS in the area. A special morning tea was to be laid on in the Mess for her, but the building could not be accessed through the front door because of the runaway steam roller was blocking the entrance… Boys will be boys one might say…]

Leading the Squadron in the March Past the A.O.C. and the “Queen WAAF” on the occasion of the presentation of the Sunderland Cup. June 1945.

[This next picture taken in the Mess with Wing Commander ‘Sticky’ Murphy pulling down the ‘dice’ meaning that operations were on and they would be ‘dicing’ with death. If the scrubbing brush was pulled down it meant that ops were ‘Scrubbed’, perhaps due to bad weather, or other reasons and the bar would remain open. Much the preferred option I am sure at that stage in the long war.]

[ There was another incident regarding the afore mentioned Hugh Boland and his love for explosives. My Dad had a miniature working replica of a cannon cast in brass that had been used for starting pre-war sailing races. It had a barrel about 8 inches long and sat on a beautiful carriage with brass wheels. Hugh would load this up with gunpowder and gravel and fire it at the steel sides of an aircraft hangar which he managed to successfully penetrate at 50 paces.

This same cannon came home after the war and sat proudly on the mantelpiece in our lounge room. At my Sister’s 21st birthday party the venue was only licenced until midnight but for Father and his cronies the party had only just begun so everybody was invited back to our house to kick on. We had rather a long hall way and after a few more drinks Father decided to fire the cannon. The hall was stripped of rugs and the weapon duly loaded with powder. The crowd gathered behind the cannon and lights were extinguished. There was a bright flash and a long tongue of flame appeared, accompanied by a deafening roar which was magnified being indoors. The cannon recoiled down the hall at high speed when there were suddenly screams “I’ve been shot”. The lights were quickly restored and there was Hugh Boland with his face all covered with what appeared to be smoke stains and grime. General pandemonium ensued until it was discovered that Hugh had not been shot at all, but knowing what was about to take place had run into the lounge room where there was an open fire burning. He had put his hands up the chimney and blackened his face with soot and ran back into the party! What a memorable evening and at age 15 I was in complete awe of these wonderful men who really knew how to party!]

Next time…

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – The War Years (Four)