I hope you got some popcorn… because we are back!

There was little information last week about the Havoc Turbinlite when I was searching the Internet.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Lo and behold!

Spotlight on amazing Shropshire RAF wartime project

Source of the article

An airbase in Shropshire played a top secret role in the Second World War. Toby Neal explains.

During the Blitz which pulverised Britain’s cities our air defences struggled to find the Luftwaffe raiders in the dark – never mind shoot them down.

And those desperate times saw an extraordinary top secret unit operating from an airfield in the heart of the Shropshire countryside using hush-hush equipment which, the boffins hoped, would help turn the tide.

The details were so sensitive that anybody breathing a word about it would quickly be moved on to another base.

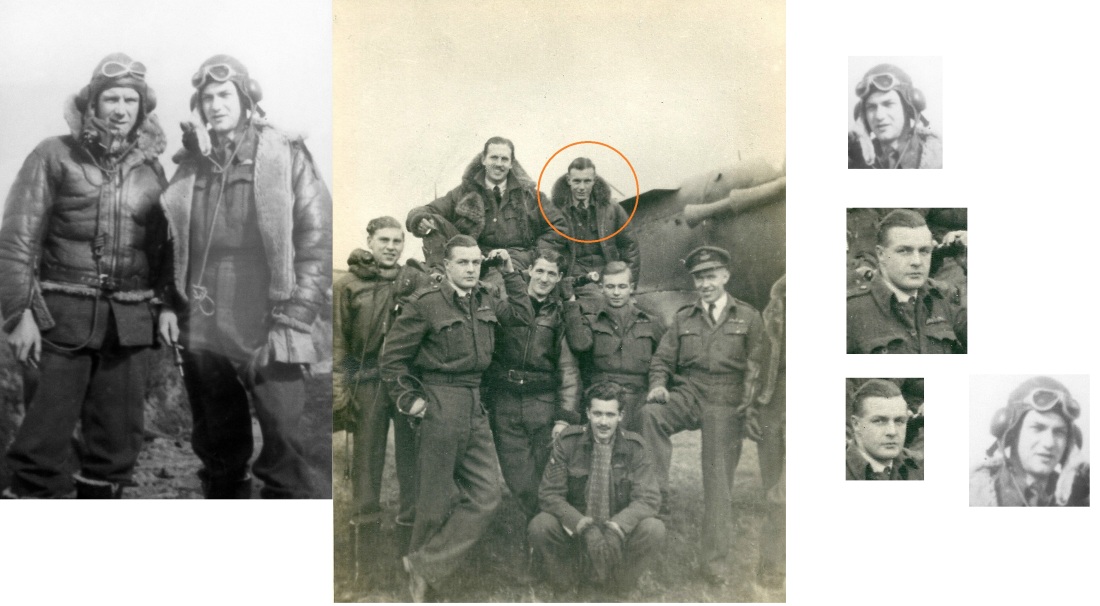

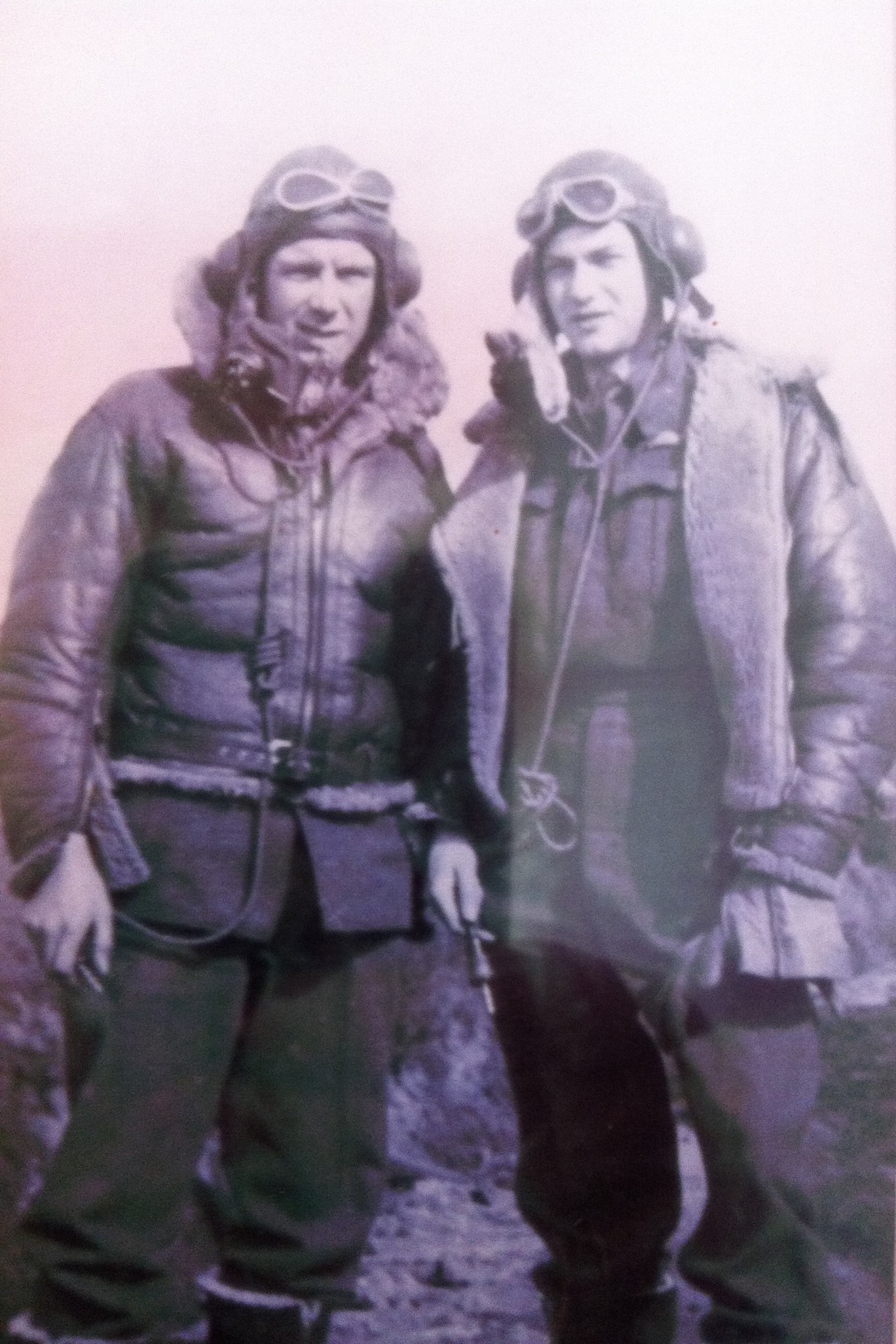

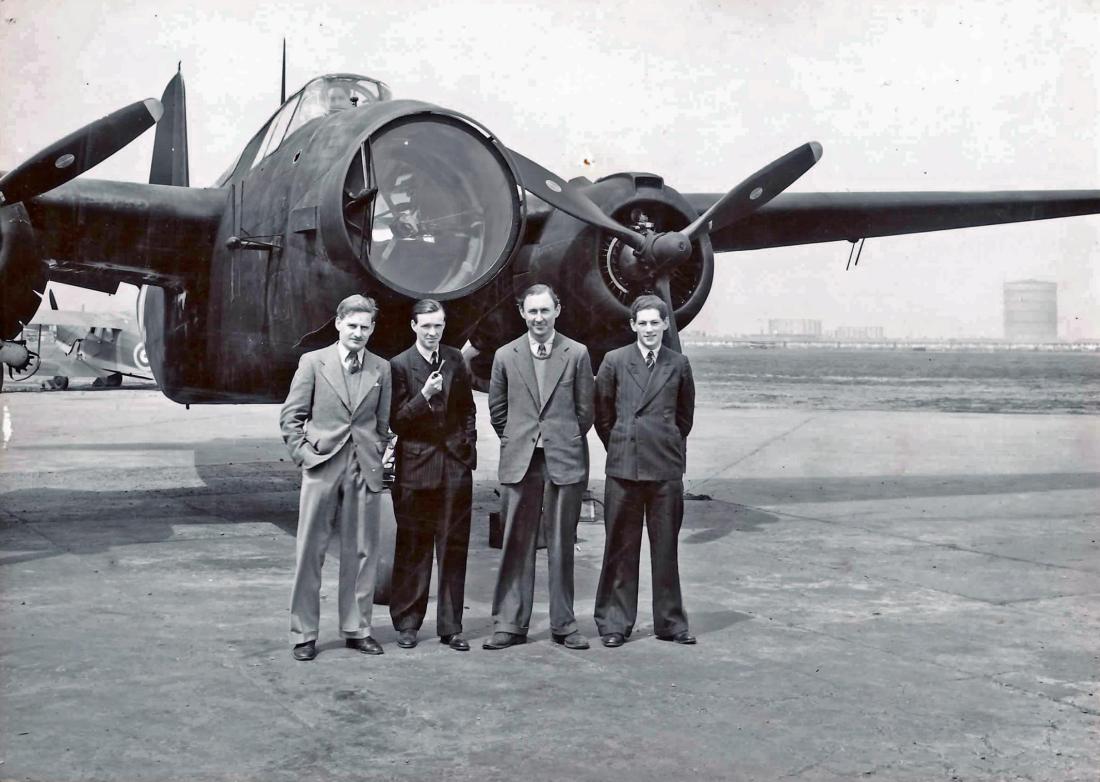

So a photo in the possession of 95-year-old Peggy Murray, of Clive, showing the mysterious 1456 Flight at RAF High Ercall, in which her late husband Bob served, is quite possibly unique.

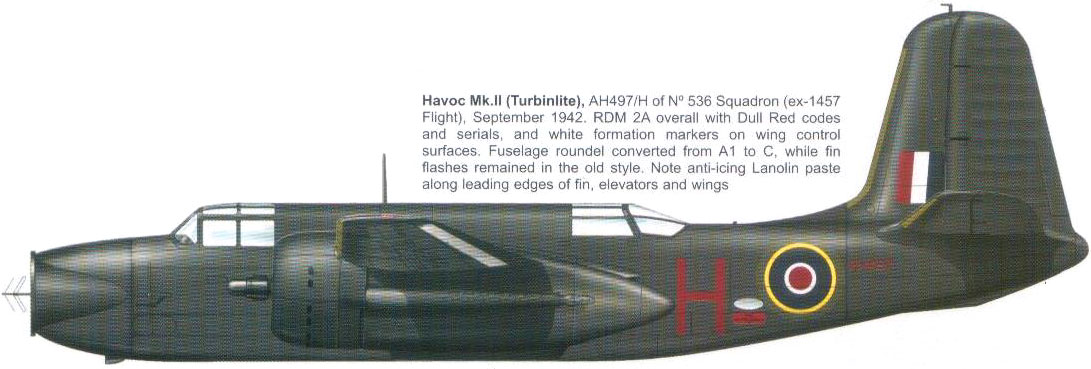

The photo, which most likely dates from 1942, shows the personnel in the team and behind them is a Douglas Havoc bomber, with the nose covered up to hide the secret equipment installed there.

Was it the latest radar? A new type of weapon? A radio antenna, perhaps?

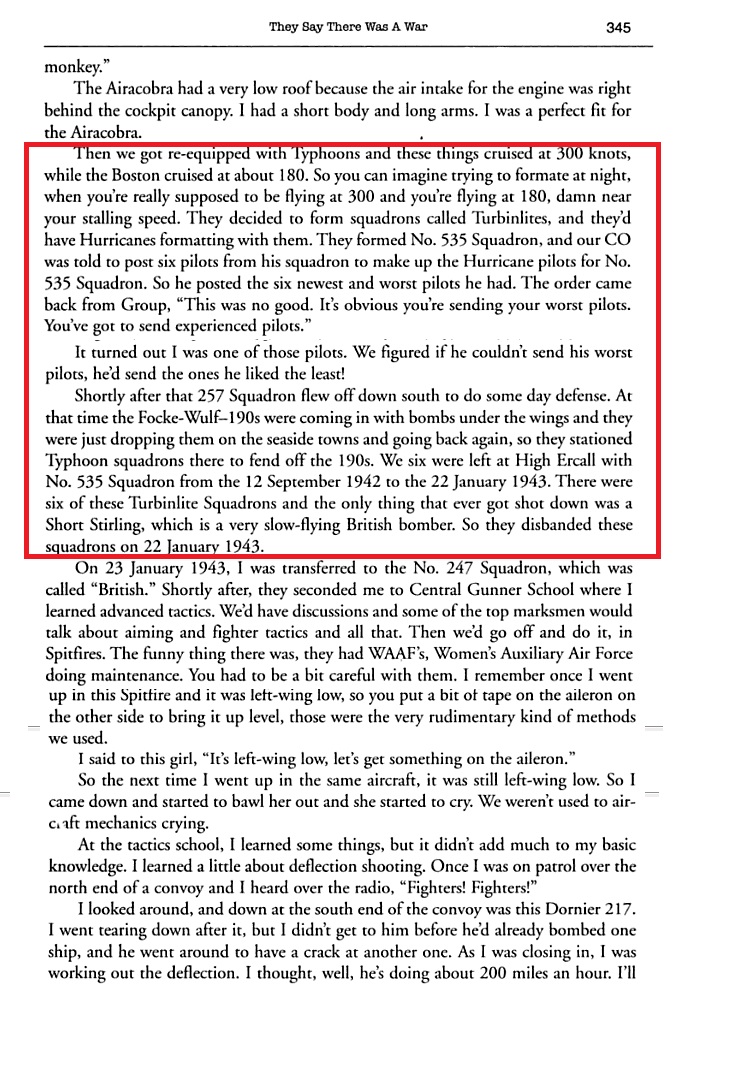

No, it was none of those things. In one of the most remarkable episodes of World War Two, the aircraft had been converted into a huge flying torch.

In the nose was installed a high-power searchlight, known as a Turbinlite, powered by batteries in the bomb bay. The idea was simple. The bomber would illuminate the German bomber and then an accompanying Hurricane fighter would shoot it down.

“I know more now than I did then,” said Mrs Murray.

“I knew they were working on something because I used to mix with the villagers. If anyone working on it said ‘Did you see that funny plane flying last night?’ they were moved the next day to another aerodrome. That happened fairly often.” The secret was, however, safe with her husband.

“He never spoke about it. I knew he was doing something. I teased him about it, but if I didn’t know, I couldn’t tell anything.

“They started working on it at RAF Shawbury and they tested it at RAF Honiley. We were there when Coventry was bombed. I heard it – the ground absolutely shook.

“I believe it was a Mosquito they were trying to adapt.” Her husband was part of the ground crew.

The Turbinlite team setted at High Ercall and the equipment was demonstrated to the King and Queen when they visited the air base on July 16, 1942.

Unfortunately, in action the equipment was not a success. There were problems co-ordinating the Turbinlite bomber and the accompanying fighter in the darkness. No kills were notched up by the High Ercall team – it was one of a small number of Turbinlite units at the time – and improvements in radar and the performance of night fighters rendered the “flying torch” obsolete.

Peggy relives her days as a signalman in her old signal box, which was at Yorton, but was re-built at Arley on the Severn Valley RailwayPeggy relives her days as a signalman in her old signal box, which was at Yorton, but was re-built at Arley on the Severn Valley Railway

Mrs Murray, whose first name is Margaret but has always been known as Peggy, still lives in the same house in New Street in which she was born on April 14, 1918.

Husband Bob hailed from Alford, Aberdeenshire, and was in the pre-war RAF, which brought him to RAF Shawbury.

The young Peggy Thomas, as she then was, met Bob at a dance at Shawbury Village Hall before the war and they married in October 1939. After the end of the Turbinlite, Bob was posted to an airfield on the south coast, and Peggy landed herself an unusual wartime job.

“They wanted a signalman for the signal box at Yorton, and I applied for the job – and got it. I was the first woman on this line.”

She did the work for two or three years.

“The shifts were 7 to 3, and 3 until the 11 o’clock train had gone through, which was the last train to stop. The line was very busy – busier than at any time. They were building up the troops on the south coast. There were all the bases. Everything came by rail in those days.”

The Yorton signal box was later dismantled and re-erected on the Severn Valley Railway at Arley.

A few years ago Peggy rode on the SVR and, in her honour, the train stopped specially at her old haunt and she was able to pay it a nostalgic visit.

“It was exactly the same,” she said.

Next time… we will take a look at this!