Updated 9 May 2023

Use the search button on the right side to look for someone’s name among close to 500 posts I have written since 2011 about RAF 23 Squadron.

Use the comment section or the contact form below to contribute.

A blog about a RAF Mosquito squadron

Updated 9 May 2023

Use the search button on the right side to look for someone’s name among close to 500 posts I have written since 2011 about RAF 23 Squadron.

Use the comment section or the contact form below to contribute.

I am trying to identify a number of photos donated to our Heritage Centre at Bransgore Christchurch UK.

I believe a number are of Jim Coley on his own and other aircrew. Is it possible someone can identify them for me?

Unfortunately we do not have the donors details just a name Cyril Chamberlain.

To be continued…

Leave a comment…

Second World War Clandestine Lysander and Intruder Mosquito pilot Wing Commander Alan Michael ‘Sticky’ Murphy DSO and Bar, DFC, Croix de Guerre

by James H. Coley

Hardback – 240pp – 234 x 156mm. Approx 30 black and white photographs.

World Rights – Fighting High Ltd. ISBN – 978-1-9998128-4-3.

Those who knew Wing Commander Alan Michael ‘Sticky’ Murphy remember a man who was an inspiration both on and off duty. Indeed, it motivated James H. Coley, who served as a navigator in No. 23 Squadron, to write a book dedicated to his commanding officer’s memory and honour.

In 1941 Sticky joined the ‘cloak and dagger’ 1419 (Special Duties) Flight, pioneering short take off and landings dropping agents into occupied Europe. It was extremely hazardous and daring work. On one flight his Lysander was ambushed by Germans, with Sticky having to fly home seriously wounded, and his exploits on a mission to rescue a comrade, John Nesbitt-Dufort, would earn him the award of the Distinguished Service Order. Such feats made him a legend in the secret and clandestine circles in which he moved, a time Sticky recalled as ‘The greatest fun ever.’

In 1943 Sticky converted to Mosquitoes, and was posted to Malta and No. 23 Squadron. Night after night Sticky led the way, following the Squadron motto ‘Semper Aggressus – Always on the attack’, which he was more inclined to translate as ‘Right lads! After the bastards!’. Sticky soon took command of No 23 Squadron, and became loved for his humanity, daring leadership, and natural charm to all. In 1944 Sticky returned to the United Kingdom and Bomber Command’s No. 100 Group, carrying out dangerous intruder operations against German night fighter bases, and it was on one such operation that Sticky flew his final fateful sortie.

It was said that those who knew Sticky never forgot his infectious laugh, his joy of living, and indomitable personality. Let there be no doubt that in any Valhalla of warriors, Sticky Murphy sits beside his contemporaries on equal terms and with a smile.

Update to this story by Mark Gilby

Cherie Dawson, the author, wrote this footnote this week.

« Footnote 15th November 2023

After I wrote this story in 2007 I attempted to find Joyce Schofield or (at least) her family, in order to find out what became of her after she lost her fiancé in the war, but all attempts at that time were in vain.

After fifteen years, just a few weeks ago I came across a piece of information not known to me before. That was the address where Joyce was living at the time Uncle Ron was declared Missing In Action, and this important information rekindled my quest. I knew that it was highly unlikely that Joyce herself would be alive as she would now be 101, but still hoped to find out that she had hopefully enjoyed a long and happy life.

This time I did find the details of Joyce’s life after uncle Ron’s death, through and with the help of a kind Englishman I connected with via Ancestry.com (his father-in-law was a direct cousin to Joyce) and sadly it was not the happy ending I imagined for her. She lived at that same address (10 Smalley Street, Burnley) for the next seventeen years with her parents (a long time to mourn a loved one) but eventually married a widower, Frank Graves in April 1961 at the age of 38. They didn’t have any children, but he had a small child at the time of their marriage, whom Joyce would have cared for. Very sadly though, Joyce died just four years later at the age of 42 in July 1965 from cancer. Not the happy end I was hoping for, but a true love story nonetheless. »

I am that kind Englishman. I have only known of Ronald « Shorty » Dawson for just over 2 weeks, since Cherie only found me on 30th October. Corresponding with Ronald’s niece in Australia has brought this brave airman closer to my heart too. Tomorrow, I will visit the Runnymede Memorial and send a current photograph to Cherie. Next year, I intend to visit Copenhagen on 21st March in his memory.

Mark Gilby

THREE LETTERS

By Cherie Daniel

THREE LETTERS

(PDF version)

For my Grandparents George and Constance Dawson whom I adored

My Uncle Ron, one of my Father’s elder brothers, was a pilot and was shot down and killed in WWII. That was all I really knew of him growing up, apart from a photo on my Nanna’s mantle of a handsome man in Air Force uniform with pale gentle eyes, like those of my father’s, and a cheeky little smile.

He had died eight years before I was even born, but if ever the war was discussed and on Anzac Day especially, I would spare a little thought for him and say a silent thank you. I’ve always had a sense of pride, as a member of his family, and felt indebted to him as an Australian citizen, because he had given his life in the service of his Country.

Then, when I was in my mid twenties and by this time married and a mother, my Father received the first of two letters from an old war comrade of Uncle Ron’s who lived in Kent, England and had been trying to track down his family for quite some time, mainly to let them know how proud and honoured he was to have served with him and also to give a little insight into his life and escapades during the war. Sadly, my grandparents had both died by this time, but I remember Dad being really excited on receiving it and of listening with great interest as he read aloud.

10th August 1978

JAMES H. COLEY

Dear Mr Dawson

I have just received your name and address from Australia (Ron Layh of Manly), and for many years have been trying to trace the family of RONALD GEORGE DAWSON, known to us as ‘Shorty’. I understand you are his brother.

I do not know how interested you are, after all these years in what happened to Shorty in UK and Malta, Sicily, Italy, France and Denmark etc. His navigator, Fergie Murray was trained with me from 1941, and with John Irvin. John and I were both 6’4” tall and I enclose a photograph of us with Shorty taken in Sardinia in early 1944.

The only other thing to tell you in this first letter is that John and I went to Denmark in March last specially to pay tribute to the memory of Shorty and Fergie who were lost there in bombing the Gestapo HQ at Shellhouse on 21st March, 1945. A ceremony of the former prisoners now surviving is held each year.

We placed flowers at Shellhouse and then in the sea near where Shorty and Fergie went in after being hit by flak from a German ship. With ex-prisoners we stood in silent tribute to their memory. I made a speech at the lunch that followed, telling the Danes about Shorty and Ferg, and have always believed that Aussie and Kiwi families should know what happened to their boys who came here and did not return.

We have just had an old squadron reunion where a Kiwi who stayed here (after the war) was present. He has just finished flying jumbos. We both knew Shorty from the Spring of 1943 and wondered if you ever heard from the young girl in the WAAF who had smitten Shorty, which caused him to stay here instead of going to the Pacific War. He was a test pilot at the Operational Training Unit where we became instructors for a time after coming back from Sardinia and used to be so shy about her as he thought we would tease him after all his talk about breeders’ permits (marriage certificates) etc.

Fergie, his navigator, was 38 when he was killed, but with his prayers and Shorty’s oaths they made a great crew and were a legend for skill and courage amongst those who knew best – us, their mates. Fergie’s widow is still alive.

We gave the Danes photographs of them both and told them what great chaps they were. The Danes hold them in great respect and were most kind and hospitable to us.

Archie Smith of Beaumaris, Victoria was the leader of the VIC formation in which Shorty and Ferg were flying at the time they were lost and Bob Ireland the leader of the 464 Squadron. He now lives in Mount Eliza, Victoria. Mick Martin, a recently retired Air Marshal, who was one of the leading Dambusters wrote to me about Shorty a few years ago.

Shorty had a happy life with us, and did some horse riding and swimming in the Mediterranean – including a freezing nude sortie with me for a bet when a crowd of us were having a stroll along the beach in mid winter.

Please let me hear from you. I have other photographs and stories of Shorty.

Yours sincerely

James H. Coley

The photograph that was enclosed showed this tiny man, (Uncle Ron) all of about 5’4”, flanked on both sides by two absolute towers of men, and apart from being quizzical, it just brought home to me the fact that courage comes in all sizes. From that first letter I gleaned so much. I found out with whom and where he served, how he lived and even, sadly, where he met his end. It was heart-warming as well to know that the Danish people still remember and honour those who fought and died on their behalf. The fact that he was killed only a few short months before the end of the war in Europe (June 1945) did not escape me either. Incredibly, I also learnt about his love for an English WAAF, and from what his friend said, perhaps his first and only love. I remember feeling a pang of pity then for that young girl who would have been just as heartbroken as his family all those years ago when he did not come home and wishing that I knew her name. Dad vowed to enquire further about her when he replied.

A picture of Uncle Ron was now starting to form in my mind of a true Australian larrikin, a short nuggety guy with no fear, who embraced life and also loved to tease his Pommy mates unmercifully, in the true Australian tradition that remains til today. My father wrote back to James Coley and within a few months received a second letter.

JAMES H. COLEY

29th November 1978

Dear John

(it would seem strange calling you Mr Dawson after your brother was so close to us)

I apologise for the delay in replying to yours of the 4th October, but I have been trying to gather together photographs and other information to put in one bundle to you, and have not yet finished, so must at least acknowledge your letter in this way.

I did not know, or at least remember, much about Ron’s family and it is interesting to hear of the survivors and that your brother Bob received one of the letters I sent to your father at the last address given to me by RAAF. Recently I heard that Ove Hermansen, the Dane who is researching everything about the Gestapo HQ raids (four of them) by mosquitoes, had heard from you or one of your brothers. He lectures on the raids to young Danes at university etc. He was most hospitable to John Irvin and myself at his home in March last, as were the surviving prisoners, liberated when the raid took place at Copenhagen.

John Irvin and Bill Shattock (my pilot in Malta and elsewhere), who both share such happy memories of Ron and Fergie Murray, have just spent the weekend here with us, and their wives. I showed them your letter and they send their good wishes to you all.

I cannot remember Ron’s girlfriend’s name, but she was a sweet little English sheila of the WAAF and he was a bit bashful about being so obviously in love, after all his tough Aussie talk (most of us were married) about breeders’ permits and such. He thought we would tease him back, but it was obviously too serious for that. He had finished his tour of duty and could have come home for the Pacific War, but I’m sure it was the girl and his warm regard for his navigator, Fergie Murray, that made him stay on and go to 464 squadron of the RAAF with Bob Ireland as C.O.

We first met him at 13 OTU at Twinwood Farm near Bedford, where we learned intruder work on Blenheims. This was a specialist sort of night destroyer operations on German night flying bases, and after our training we all went to Malta on 23 Squadron, where Ron loved the sun and sea, and as you may remember he could swim like a fish. We were hard up for grub though and Fergie lost about two stone, while I was 6’4” and weighed less than 140lbs.

Ron and Fergie used to quarrel to hide how much they respected each other, and on one trip were posted missing, but turned up after a great feat of navigation and piloting through moonlit mountain passes, after losing an engine strafing near Foggia in Italy. Ron made a miraculous landing at Palermo in northern Sicily on a short airstrip by the light of headlamps from a jeep. Our NZ flight commander went there in daylight in a Spitfire to see them and could not get down the first time. Next time out Ron shot down a Dornier 217. We could never understand why he was not decorated, but he was no respecter of persons in authority, and thought everybody ‘Pommies’ except we, his mates. I flew with him off the Bay of Naples and both engines cut out and we dropped towards the sea, but at the last moment he got them going and we did not have a watery grave that day.

More when I get a chance, but MERRY CHRISTMAS to you all.

Yours sincerely

Jim Coley

It was obvious from this second letter that Uncle Ron was revered by his compatriots for his bravery and piloting skills and loved by his friends for his uniquely “Aussie” personality. Unfortunately though, Mr Coley couldn’t remember the name of the young girl who had stolen Uncle Ron’s heart and this was the last correspondence my father received from him.

The two letters were eventually confined to an old brown leather pouch that had lived at the bottom of my father’s wardrobe beside his workbag, for as long as I could remember, where he kept any papers or correspondence of importance to him. They stayed tucked safely away there for another thirteen years until my dear father passed away.

On rediscovering them I was once again inspired and showed them eagerly to my two now grown up daughters, my friends and my three younger brothers, the youngest of whom didn’t know of their existence. I recall him being especially proud and touched by Uncle Ron’s brave deeds, as he is also in the Armed Forces and empathised with him most deeply.

Another sixteen years have passed since then, don’t ask me where they have gone, but earlier this year on a recent but rare visit to my Aunty Joan’s (she lives over 600kms away), I decided to take her copies of the letters as I wasn’t sure if she had seen them or not. While we have always lived a long way apart, Aunty Joan and I have remained close and she is now the only surviving member of my father’s once large family. She was most thankful and happy to have them, as she didn’t remember seeing them before, but she had something even more wonderful to show me. A few months earlier when she was going through some old papers she found Uncle Ron’s last letter home to his mother.

18th December 1944

Dear Mother

It’s quite some time since I’ve written to you and quite a lot of things have happened in the meantime. I won’t try to explain why I haven’t written but I should be able to give you some idea of my past activities.

Well I am back on my second tour of operational duties. Before I started this tour, which was about a month ago, I was given the preference of a ticket to Australia or another tour of Ops, well I chose the latter for reason that you will see later. Since you last heard from me, as you will see from my address, I have been made up to Flying Officer. Ferg my navigator has also been made up to the same rank. He is the same navigator as I had on my last tour.

I have been receiving your parcels regularly, the last one arrived about a week ago. I also received Joan’s Christmas cable about the same time. Please convey my thanks to the Bangalow Welfare.

Well Mother I suppose you have been wondering why I turned down the offer of a ticket back to Australia, it took quite a lot of deciding and at the time I thought, whichever I decided I would probably be sorry, especially being away from home so long. Anyway I should know my own mind. The fact of the matter is, which will probably come as a shock to you, I became engaged about two months ago. Now that you have heard the worst I had better tell you a little about her. Well her name is Joyce Schofield and she comes from Burnley, Lancashire. Joyce has just turned twenty-two and is a member of the WAAF. I first met her about seven months ago at the same camp as I was stationed during my rest period. I have been to her home several times on leave and met her people. They are quite a nice family and just ordinary people and I’m sure you’d like them. I’m sure if you knew Joyce too you would immediately be with me in saying that I have done the right thing. I wont go into details to tell you how much I think of her, I’ll just leave that to you own imagination.

There is nothing much more of any importance happening as far as I am concerned, since you last heard from me so I’ll end up here, but remember the longer I stay here the better off I am. At least I can save more money because I don’t pay any income tax and believe me I’ll need it. Well Mother cherrio for the present and I hope everything is OK at home.

Lots of love Ron

Finally the mystery girl had a name, ‘Joyce Schofield’, and she was not just his girl, but his fiancé. From the date on the letter and the age she was at the time, I calculated that she would be eighty-five years old now, if still living. If so, I know she would remember Uncle Ron and I would love her to be able to read the three letters. Finding out her name is what actually compelled me to put pen to paper.

As you see, this story has been a long time in the telling. It actually started just over ninety years ago on 18th September 1917 when Uncle Ron was born in Bellingen, a small country town in NSW. One of nine children (seven boys and two girls), he grew up in hard times and was only twelve at the onset of the great depression. I called upon Aunty Joan to fill in some personal details of his early years and these are some of her childhood memories of him. They are, as she says, nothing but fond although scrambled and dim, as she was only twelve when he went off to war. He worked on a farm and his best mate and a couple of his brothers rode motorbikes around town, they had their own little ‘gang’ going. He was kind and generous with his time and where the others wouldn’t, Ron would always give Joan a ride on the back of his bike whenever she wanted. His best mate already had his pilot’s licence and I’m guessing that’s how Ron discovered his own love of flying. Jobs were scarce in the country so in his late teens he went to Sydney with two of his brothers, looking for work. They lived in a boarding house at Drummoyne and Ron got a job at the Nestles Chocolate Factory, where most of his wages went to pay for flying lessons. (That explained to me why one of the documents I found during my research listed his occupation at the time of enlistment as ‘confectioner’. I thought it a strange job for him to have, or perhaps a misprint. From my knowledge of him, which was almost entirely through those first two letters, he didn’t seem suited to that kind of work). On occasion, while working there he would send chocolates home to his Mother, who had great trouble hiding them from her large brood and rarely got to keep any for herself. Joan remembers fondly too, receiving the largest Easter egg she had ever seen from him one year. I’m sure she would have shared it with all her family though, as like her brother Ron before her, generosity runs strongly through her veins. He signed up at the outbreak of the war and with a number of other Australian flyers, was sent to England to fly with RAF squadrons.

A debt of gratitude is owed to James Coley, wherever he may be, for making the effort to find Ron’s family and provide us with a real and powerful image of his last few years. Perhaps the writing of this story will repay it in some small way.

The picture of Uncle Ron is complete now in my mind and I want to share it with others, so that they too may have an insight into the spirit of an “ordinary Australian” but yet an extraordinary man. There are, of course, thousands of stories like this one to be told, of brave Australians who went off to war to fight for their country, families and way of life and never made it back home, this is just one.

Another special bond exists between my uncle and myself, in that the short gene he inherited, was passed down but skipped my Father, missed my three brothers (two of them are over 6ft) and landed squarely on me. Both my daughters are taller as well and the younger one delights in being able to rest her chin on top of my head, but I don’t mind when they tease me and call me shorty; it makes me very proud to bear the same name. Here’s to you Shorty Dawson.

Uncle Ron on 23 Sqd Malta

(third from left sitting)

Written 23rd October 2007

Published online 11 November 2023

Note

Paul Rapson has identified his Grandfather in a comment. See the comment section below.

With the kind permission of the author, One Man’s Addiction to Flying will be published online each and every day. After the online publication is completed, a PDF version will be available to download.

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – Introduction is here.

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – The War Years (Part One) is here.

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – The War Years (Part Two) is here.

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – The War Years (Part Three) is here.

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – The War Years (Part Four) is here.

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – The War Years (Part Five) is here.

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – Post War Flying

The Leicestershire Aero Club had reformed after the war, first at Ratcliffe and then at Stoughton. I was on the committee and, in 1951 was Chairman. When firing a Verey pistol from the roof of the club house to start some event in a big display we were running, the gun exploded in my hand and made rather a mess of it and also my face. A piece of the barrel went into the thigh of an RAF airman helping the display and did him no good at all.

I had got rather tired of noisy aircraft, and in Mosquitos, with a pair of 1,000 horse power Merlins with open exhausts on each side of the cockpit, the noise was really quite something. Gliding was something which appealed to me as being really quiet and I joined the Leicestershire Gliding Club which was operating from Ratcliffe Aerodrome. I enjoyed this very much and got my A, B and C certificates and went on many week-end camps to hill sites.

It was rather fun to be able to chat to someone on the ground from 500 feet in one of the open cockpit training gliders. Rather late on one summer evening I was drinking scotch rather morosely in the Club bar when a man named Bob Loorimer, a local hosiery producer, came in. He asked me why the gloom and I explained that we had just broken our last serviceable glider. ‘Don’t worry’ he said, ‘I’ll buy you a new one-how much are they? I told him 500 pounds and he wrote a cheque cut on the spot. We finished up the bottle and next morning took the cheque into the bank rather hesitantly, but it was passed, and we bought a new Olympia glider which his wife later christened. I was made a life honorary member. I should think so! To progress much further in the gliding world meant doing cross-country trips, and in turn, this meant sharing with another pilot, taking turns to tow the trailer and collect the glider from wherever. Very time consuming and I was getting involved in towing the horse trailer for my children’s gymkhana activities. So that was the temporary end of my aviation activities.

[This not quite how I remember this! There was a ghastly flying accident when the release gear on the towing wire which was used to launch the gliders malfunctioned. The glider was unable to separate from the wire and was pulled down into the ground killing the pilot instantly. I think my Mother, who had been very patient up to this point, put her foot down. There were by then 3 of us children who needed their Father and having survived the war Mother was not about to let him kill himself in a glider accident. I am not totally sure that the line my Father was shooting here was strictly tikiti-boo, but Dad is not here now to correct the record!]

In 1974 I retired from business and went to live in Blakeney, only 10 miles from Little Snoring.

In 1983 my wife said to me that I looked as if I needed a challenge in life. “What about getting your pilot’s licence back?” So I accepted the challenge and went to talk to the Norfolk Flying Club, who were flying from an RAF airfield at Swanton Morley. They had the use of the grass airfield and one hangar which the RAF was not using. On their advice I first went for quite a stiff – and expensive medical test required by the Civil Aviation Authority before a Private Pilot’s licence can be issued. Not much point embarking on a very expensive training course only to be failed later on medical grounds. This proved to be O.K, and I started on the necessary flying training, The Authority had recently tightened up their demands owing to a large number of pilots who were killing themselves soon after getting their licences, accidents which were put down to inexperience. The new requirements for the number of flying hours was a minimum of forty-three, but as I went to see them with my log books and, in spite of the thirty-seven year gao, because of my previous experience, I was granted a concession of a minimum of twenty-eight hours which saved me a lot of money.

The aircraft used for training by the Club were Cessna 152’s. These are small metal, tricycle undercarriage, dual control machines. There are thousands of them all over the world and they are treated rather like motor-cars. Fill them up with petrol and oil, kick the tyres, make sure nothing is falling off, press the self-starter and off you go. When I reported for my first lesson, my instructor suggested that I wheeled the aircraft out of the hangar, carried out the routine checks and waited for him to join me. This was quite a surprise to me because my last powered flight had been in a Mosquito which had been most carefully checked for every function and the necessary form presented to me by the Flight Sargent fitter for my signature before take-off. Oh well!!

Being a fairly cautious character, as regards aircraft anyway, I was reasonably through in my checks, especially flying controls. During my time at Cambridge I was asked to flight test a Tiger Moth which had emerged from a major inspection. For some reason I did not test the controls and, as soon as I got airborne, I found that they had connected up the wrong way. This made life very interesting and I approached the ground for a landing with considerable caution. All was well, but it taught me a lesson.

I was relieved to find that flying, like riding a bicycle, once learned is never forgotten. A little polishing here and there but no major problems. I was fortunate to arrive at the Club when they had a very good team of instructors. I was allowed to go solo after three hours and found no problem with the flying training syllabus. R/T (Radio Transmission) proved to be a major problem for me. Swanton Morley was at the time surrounded by very active RAF bases from which there was almost continuous flying. These bases each had their own controlled area and their own frequency. These frequencies were obtained by twiddling a knob until the right number came up, just like a radio set. Swanton had its own frequency and, on leaving the vicinity of the airfield, it was necessary to call them up and tell them that you were switching to such and such a frequency. When on cross-country flights, it was necessary to call up the next controlled zone and say, for instance, “Marham, this Golf- Bravo-Foxtrot-Sierra-Romeo on a student training flight in a Cessna 152. My present position is…my height is…my course is…and my estimated time to enter your controlled zone is….Request your permission to proceed. Over.”

At first I used to get completely tongue-tied half way through the transmission and have to start again. Most of the controllers, especially if they were female, were pretty tolerant but some got a bit shirty. If you were accepted you were then told to “stand by on this frequency’. At the busy stations and at Norwich Airport there was fairly continuous chatter going on and if your own call- sign came up you were expected to reply immediately. Since invariably you were endeavouring to cope with several other problems at the same time, this was not always as immediate as the controller expected and they tended to get a bit tetchy – especially if it was a message from an RAF base such as “Golf Sierra Romeo. This is Marham. Alter course immediately 90 degrees to port. There is fast traffic approaching from your starboard side. Acknowledge. Over”. A few minutes later five or six Tornadoes or similar would scream past at 650mph – sometimes uncomfortably close. When peace again reigned the message would come: “Golf Sierra Romeo. Resume your original course” by this time you were almost certainly lost to the wide and trying desperately to pick up landmarks which were not on your prepared route.

One of the passing-out tests was a triangular cross-country, landing at two other airfields and getting a signed report that proper procedures had been followed. I chose Ipswich and Cambridge. When I was working out my flight plan, I realised that I should have to make sixteen frequency changes, some of them in a short space of time. It seemed to leave little time for flying the aircraft and map reading, but it all worked out in the end and I got my two pieces of paper. All this flying was done by map and compass, just as in 1937. How I longed for the sophisticated equipment we had at the end of the war, and a navigator to do some of the work.

I then had to tackle a passing-out test by a Civil Aviation Authority Examiner. He was reckoned by the Swanton gang to be a bit of a grumpy bastard, but I found that he was nearly as old as me, that we had a lot in common and we got on well. The two hour test included verbal tests on the ground concerning the aircraft and then a very thorough flying test including spinning, blind flying, forced landings, cross wind landings and take-offs, etc. I passed. The most trying part of all were the ground examinations. I had attended several lectures on various subjects and I had been through and through the official booklets. but my brain seemed to have lost a lot of whatever capacity it once had for absorbing knowledge. I was frequently up at 6.00am through the summer studying various subjects. There were three exams of two hours duration. With only a very little cheating with cribs, I passed all three and was awarded my Private Pilot’s licence. At 67, one of the oldest members of the Flying Club.

I was then entitled to take passengers and, using the Club’s four-seater Cessna 172, I took up several friends to show them the coast and their houses from the air. My wife Sheila came with me on several occasions and took some very good aerial photos. I was also able to use my licence in Australia and in 1995 I hired a Cessna from the Sunshine Coast Air Charter at Caloundra in Queensland and Sheila again got some excellent photographs.

In 1988 I had a sudden urge to try flying a helicopter and had a hour’s lesson from a company at Norwich Airport. Very, very difficult and very, very expensive. End of urge.

I enjoyed it all immensely, but in the summer of 1989 I caught myself making some minor errors and being a bit forgetful. Since I had not had an accident or damaged an aircraft in my 3000 hours of flying I felt the time had come to pack it in while the going was good. I made my last flight in Golf-Bravo Hotel Alpha Victor on 29 September aged 73 and very grateful for all the fun that flying had afforded me.

[ Father had enjoyed his ‘addiction to flying and at the end the war his log book credited him with 2,874 hours and 30 minutes of actual flying time. This was an astonishing total. With some 72 operational sorties the fact that he survived in one piece was amazing. The hours that he flew gliders and light aircraft are sadly not recorded, but he fulfilled his dream of flying in a big way!]

Dad died peacefully on 26 November 2012, in his sleep, at the ripe old age of 96. He was tired. We scattered his ashes from a boat in Blakeney Harbour. He would have flown over this harbour many times as he made his way to and from Little Snoring airfield in 1945. He loved to sail there in later years, especially after his retirement. As we drifted slowly out towards Blakeney Point on the ebbing tide, I read Psalm 139 as the family said our farewells. It is known as the airman’s Psalm. Part of it is quoted on the following page (the emphasis is mine):

Psalm 139

¹ O LORD, you have searched me and known me!

2 You know when I sit down and when I rise up;

you discern my thoughts from afar.

3 You search out my path and my lying down

and are acquainted with all my ways.

4 Even before a word is on my tongue,

behold, O LORD, you know it altogether.

5 You hem me in, behind and before,

and lay your hand upon me.

6 Such knowledge is too wonderful for me;

it is high; I cannot attain it.

7 Where shall I go from your Spirit?

Or where shall I flee from your presence?

8 If I ascend to heaven, you are there!

If I make my bed in Sheol, you are there!

9 If I take the wings of the morning

and dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea,

10 Even there your hand shall lead me,

and your right hand shall hold me.

11 If I say, “Surely the darkness shall cover me, and the light about me be night,”

12 Even the darkness is not dark to you;

the night is bright as the day,

for darkness is as light with you…

Next time…

A complete version in a more readable PDF file.

With the kind permission of the author, One Man’s Addiction to Flying will be published online each and every day. After the online publication is completed, a PDF version will be available to download.

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – Introduction is here.

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – The War Years (Part One) is here.

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – The War Years (Part Two) is here.

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – The War Years (Part Three) is here.

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – The War Years (Part Four) is here.

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – The War Years (Part Five)

Sir,

I am directed to refer to Air Ministry letter, number as above, of the 2nd April and to inform you that the American Authorities have notified their final approval of the award of the Distinguished Flying Cross to you. The a ward will be announced in the Royal Air Force Supplement to the London Gazette to be issued on 14th June, 1946.

Doubtless you will receive the appropriate decoration from the American Embassy, in due course.

I am, Sir, Your obedient Servant

American DFC for Wing-Commander

Wing Commander S. Philip Russell, DFC, of 56, Romway-road. Leicester, has been awarded the American DFC for outstanding services in co-operation with the American Forces in Sardinia.

Wing Commander Russell is the son of Mr. and: Mrs. S. H. Russell, of Ratcliffe -road, Leicester. He received his British DFC from the King at an investiture at Buckingham Palace. This award was made three years ago when Wing-Commander Russell, then a squadron-leader, had 41 sorties to his credit.

[ Copy of one page of Dad’s logbook. Note the ‘Duty’ column – Flying from Malta shot down JU 88 near Tunis. Other activity including setting fire to petrol tankers mentioned on page 15. Note also number of flying hours 2,480.]

Davis West’s Addition

‘But Little Snoring would keep calling her aircrew back, throughout all their lives, as a site of pilgrimage, and to their children and their children. Neither Squadron nor airfield would ever be the same again.

Read all the diaries, see the hopes realised of surviving tours, the lives lost, then stand on the airfield out by the control tower after dusk and hear in the howl of the wind maybe a faint roar of twin Merlin engines, and you will see those mosquitoes with their aircrew again, leaving Little Snoring perpetually for the last time… stealing into the night sky, forever blue.”

[Reading his account of the time in Sardinia and the American squadron that was based there it might be understood. that the medal was for arranging great parties, but I think in fairness it may have had much more to do with his liaison role and meeting and working with two Generals. When trying to find out a little more about the Citation for the award it was very difficult to get information about American medals given to British servicemen. However, the email reply did explain that these medals were not handed out lightly and any person being awarded such a high honour were “very brave men”.

On the next page is part of an email from Pete Smith to me. Earlier in this narrative you will have seen letters between Pete’s Father Tommy Smith, who crashed and was badly burnt, and my Dad. Pete takes a trip down memory lane (as I have often when returning to Norfolk) and visited the old airfield at Little Snoring. It is still used for light aircraft and the old control tower still stands, as do the aircraft hangers. It is a moving account and I include this with Pete’s kind permission. We are indeed most fortunate to have had such brave fathers.]

Pete writes…

So that year, on my birthday in December 2006, instead of working, I did something for me; I drove across to Little Snoring for my first visit to the airfield. I followed the way that Dad had described from his first ever visit there, past the royal estate at Sandringham, or the back entrance, and on to Snoring.

As I drove around the last corner and saw the first huge T2 hanger my heart skipped a beat, all the hair stuck up on the back of my neck…and yet it felt like I had almost come home, a place so comfortable and familiar. I went to see Tom Cushing* and when I left took the pictures of the airfield, and stood at the end of the runway, looking out towards the north sea, with the cold wind roaring in my ears, staring for all I was worth into the darkening blue of the coming night sky… and the wind, it sounded like Merlin engines roaring as the throttles opened up and looking until my eyes hurt, I could see them, one at a time just disappearing from view. My Father took off from Little Snoring and would never return there operationally as a fighter pilot…like Sticky and Darbon, and 7 other squadron crews, but he was alive.

Make no mistake, our Fathers were true blue, in the finest tradition of the RAF- me, I had the best birthday I had ever had. So, in the longest way ever, those paragraphs were written by a Son, me, written with real sorrow that I had neglected to take an interest in this part of my Father’s life, the seminal part of his life, where every operational night, death was the third member of the crew, and death would only come so close once more in his lifetime.

Tommy was most proud of being one of the pilots of the fighting 23rd, and a guinea pig and then an officer, in that order. So the remaining few, Phil, George, Buddy, Jim, Don and Norman from 23 hold a special place in my heart, they knew Tommy when he wasn’t burnt and when he was young and fighting fit, literally. With their passing the story and memory of my Father will be consigned to the history books, no longer an oral tradition by people that knew him then, but a historical event, written about in only a couple places. So there you have it. But in context, retrospectively, we are possibly the luckiest children in the world.

best

Pete

[ The Cushing family owned the land on which the airfield was built. Tom Cushing was only a young boy when the war was being waged and now continues to farm the old airfield and has a small museum containing memorabilia of 23 Squadron. He also co-authored a book called ‘Confounding the Reich’ with Martin Bowman.]

[ This book covers in more detail the work of the 100 Bombing group and is described thus:

On 23 November 1943, 100 (Bomber Support) Group of RAF Bomber Command was formed. The object was to consolidate the various squadrons and units that had been fighting a secret war of electronics and radar countermeasures, attempting to reduce the losses of the heavy bombers and their hard pressed crews – in Bomber Command. This secret war involved the use of air and ground radar’s, homing and jamming equipment, special radio and navigational aids, and intruding night-fighters to seek out and destroy their opposite numbers, the Ju 88s and Bf 110s of the Nachtjägdgeschwader who defended the night skies of the Third Reich with ever increasing success.

The book contains many first-hand accounts from pilots and crew and provides a fascinating record of 100 Group’s wartime history.]

Next time…

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – Post War Flying

With the kind permission of the author, One Man’s Addiction to Flying will be published online each and every day. After the online publication is completed, a PDF version will be available to download.

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – Introduction is here.

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – The War Years (Part One) is here.

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – The War Years (Part Two) is here.

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – The War Years (Part Three) is here.

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – The War Years (Part Four)

In December our C.O. ‘Sticky’ Murphy, of whom more later, went missing and I took command of the Squadron with the rank of Wing Commander.

In January, we became part of No.100 Special Duties Group. This Group operated from a number of airfields in Norfolk, with Headquarters at Belaugh Hall. The Group had been formed with the primary duty of reducing the escalating losses being suffered by our heavy bomber groups over Germany. Our own part in the activities was to keep on doing what we were used to, but having our targets related to the general scheme of the group. Other squadrons were flying aircraft fitted with gear to jam both radio and radar transmissions from German bases, others set out on ‘spoof’ or misleading raids on imaginary targets, and yet others flew on imaginary targets dropping ‘window’ which created the effect on German radar of a very large force. We also had to take on another activity of actually escorting the bomber force – not an easy task on a dark and dirty night with a lot of trigger-happy rear gunners in the bomber stream. As Squadron C.O., I used to attend the daily briefings at H.Q. and it was fascinating to watch the plot being hatched out, and then, on the next day to be able to see what results had been achieved. It all worked out very well and the losses in Bomber Command fell dramatically. The Germans very much resented our efforts to prevent their night-fighters becoming airborne. The aircraft flak was increased heavily and we lost rather a lot of crews. We were quite often within sight of the mainstream bomber attack and a big raid was a most dramatic sight.

Caption

The aircrew of 23 Squadron, home at last, in front of one of our Mosquitos at Little Snoring, Norfolk. Dec.’44.

[As previously mentioned Tommy Smith was one of 23 squadron pilots. His son, Pete Smith, had this painting commissioned to record his Father’s brave action in which he was shot down. It shows the sort of activity the squadron was involved in suppressing the enemy night fighter activity in the closing stages of the war. Note the 4 x .303 machine guns in the nose had been replaced with a radar cone.]

What must surely be one of WWII’s most extraordinary acts of bravery occurred on the night of 16th/17th January 1945 when F/L T A Smith and F/O A C Cockayne were on an ASH patrol over Stendal. Flying Mosquito FB.VI RS507 (YP-C). They inadvertently stumbled upon the German airfield of Fassberg on their return trip, fully lit up with aircraft taxiing. Taking full advantage of this situation, F/L Smith went straight in to attack, destroying one Bf.109 on the taxiway and another two as they attempted to take off. RS507 received ground fire hits to its starboard engine during the chase down the runway, Smith feathering the prop, but continuing to press home his attack. Knowing that there was no way of saving their aircraft, Cockayne was ordered to bale out, but sadly lost his life in the attempt. F/L Smith fought gallantly to bring his Mosquito down into snow with minimum damage, but the aircraft hit trees before striking the frozen ground and a furious fire broke out, with Smith trapped in the wreckage. Against all the odds, he survived the crash, albeit with terrible burns, and saw out the war as a prisoner of the Germans.

I have to admit that when the end of the war came, I was extremely relieved. Courage is an expendable thing and mine was just about expended. With the exception of my time in hospital, I had been flying continuously from the outbreak of war and had completed seventy-two operational sorties (considerably more than the normal thirty sorties per tour applied in Bomber Command) and I had had enough – and then some.

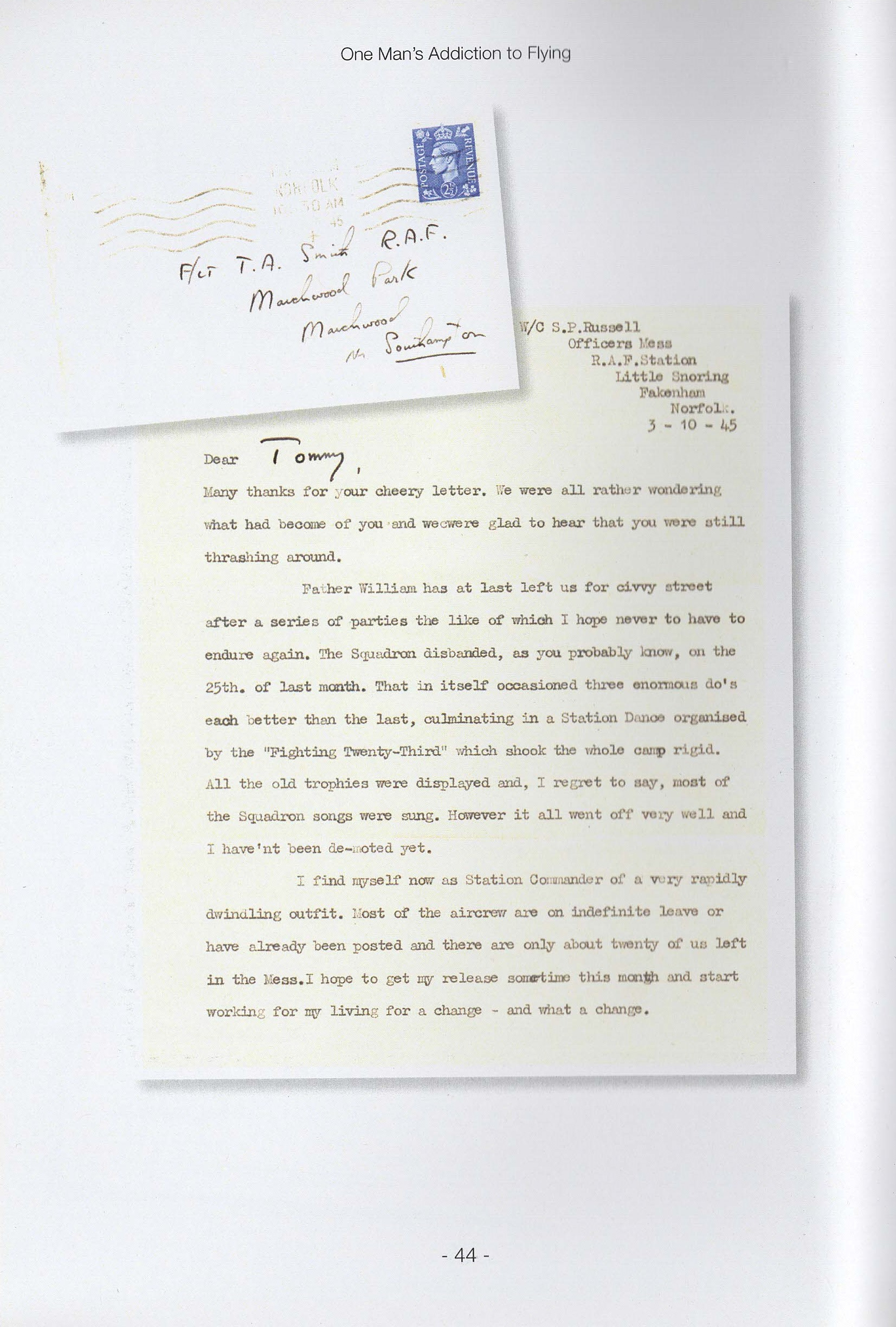

I flew my last sortie on 15 April, 1945. Soon afterwards, our sister Squadron No. 151 was disbanded, and as Senior Officer remaining, I became Station Commander of RAF Little Snoring – a lovely title! As such I had to take one or two rather large parades, including a march-past before the Queen WAAF, who had come to Snoring to present the Sunderland Cup to our own WAAF section for efficiency. We then proceeded to have enormous parties to dispose of the very considerable accumulated Mess Funds – much appreciated by all the local friends we had made. In September, the Squadron was disbanded, I was demobilised, given a demob. Suit and a felt hat and sent on my way to Leicester, broke to the wide [flat broke!] but all in one piece.

I went to see the King to collect my DFC and also to see the American Ambassador to collect the American DFC which I had collected somewhere down the line.

I was exceptionally lucky in my Commanding Officers, All regular RAF and all career men. The war was what they had been waiting for so that they could start climbing up the career ladder usually by stepping into dead men’s shoes. Group Captain B.R.O’B. Hoare (Sammy) was an incredible character with an enormous handle-bar moustache. He had lost an eye when a duck came through the windscreen of a Blenheim he was flying. Against all the rules he continued to fly but his one-eyed landings (especially in a Mosquito- not the easiest of aircraft) were something to behold and his navigators had to be very brave men indeed-not only because of his landings but because he always selected the most dangerous of the night’s targets. He created such an impression at Snoring that, when he was killed, a memorial stone was erected in the local churchyard to his memory. He made me cross because he could always beat me at squash, one eye or not.

Wing Commander Wykeham-Barnes, who took us to Malta, was not only a very brave man but also a very bright one. Having survived a terrific fighting war (and my attempts at drowning him) he stayed in the RAF and went right to the top.

Wing Commander ‘Sticky’ Murphy was another one without any fear. Before he came to our squadron he had spent many months flying agents into and out of France in Lysanders. They eventually decided that he had had enough when he just managed to return to the U.K. holding a finger over a bullet hole in his throat. Fearless, bursting with enthusiasm and born leaders of men, what a fine example they were to we amateurs who had to follow them.

The other thing I should mention before I leave the war years is that my old friend Bob Marks, with whom I flew to France pre-war, was posted to a light bomber squadron at the beginning of the war and was shot down while laying a smoke screen during the dreadful failure of the Dieppe landing. He was rescued and taken prisoner. When he was released at the end of the war he came to stay with me in my quarters at Snoring and I taught him to fly again. He applied for a posting to the Development Squadron at Martlesham and, shortly after his arrival there, he was killed while testing a German aircraft. I was not popular with his Mother.

[ What Dad does not say here is that this was his closest friend who he had grown up with. He and Bob used to make rafts out of bits of wood and set sail across a pond in the Mark’s back yard and they had many other childhood adventures. They went on holidays together and his loss must have been incredibly painful. The joy of surviving the war only to be killed when hostilities had ceased is even more tragic. Dad lost most of his red blooded friends in the war and it must have been a very lonely time returning to Civvy Street. It was especially hard when some who had not enlisted had grown sleek on war profits.]

[Recently I had Dad’s medals mounted and framed with a picture of 23 Squadron and Dad, then a Squadron Leader, taken in Kalta 1943 (front cover). The medals are described below in the caption. I also used a couple of pages from his log book enlarged to make the background. They make interesting reading and you will see on page 48 a clearer example of the ‘Duty” column where he records shooting down an enemy aircraft and strafing petrol tankers.

I believe it was unusual for British pilots to be awarded an American DFC but the newspaper cutting on the next. page indicates that it was awarded for: ‘Outstanding services in Co-operation with the American Forces in Sardinia”.]

Caption

Medals display From Left to right DFC, 1939-45 Star, Air Crew Europe Star and Clasp, Africa Star and Clasp, Italy Star, Defence Medal, War Medal, Air Efficiency Award and the American DFC

Next time…

One Man’s Addiction to Flying – The War Years (Part Five)